Beyond Place Cells

13 Nov 2017Thanks to O’Keefe and Dostrovsky 45 years ago place cells were discovered in the hippocampus. Since then people have been studying the neurophysiology of neurons to see how place, among other features of the world around us are coded. In this #SfN17 session presenters were urged to move ‘Beyond place cells’ and thankfully many have been doing just that for a number of years. However, many questions remain about mechanistically how the hippocampus and associated structures process for coding environmental features.

Source: http://www.frontline.in/multimedia/dynamic/02171/fl14_nobel_medicin_2171449g.jpg

There were many highlights from this session which featured many exceptional neuroscientists including Drs Carolyn Barnes, Nachum Ulanovsky, Edvard Moser, Mayank Mehta, Jeffery Magee, and Dmitriy Aranov. A few of those highlights are covered below.

Dr. Barnes, whose maze was the first behavioral apparatus I used, has been a champion of translating information learned about place cells from rats to higher order species, in particular monkeys. This is important to show what learned in rodents translates to humans. Dr. Barnes and her lab utilized a method for assessing cellular plasticity markers known as Arc catFISH. The method was employed following real or virual space exploration and examined expression in the dentate gyrus (DG), CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus. All three regions had increased levels of Arc for real and virtual exploration compared to control monkeys, however only the CA1 region was elevated for the real exploration over virtual. A similar result had been shown previously in rats, a win for scientific findings in one species holding for others. The data next revealed that the proportion of CA1 neurons active in the real exploration as a total of all CA1 neurons was three times lower in the monkey than in the rat. One interpretation is that the monkey may be able to code for more space than the rat. This has yet to be tested explicitly, but would prove informative as the spaces both species utilize experimentally are small relative to real-world environments they traverse.

Dr. Ulanovsky was second and his work in bats moves from small spaces to larger ones more naturalistic to see how place cells and other cell types function. One of his experiments recorded neurons as bats flew down a long 200 m tunnel. He found single neurons to code for several ‘places’ along the tunnel. Further neurons could code for a small meters wide segment of the tunnel and large segments 10s of meters long. Perhaps this is more naturalistically how place cells work in our CA1 as we navigate the conference centre.

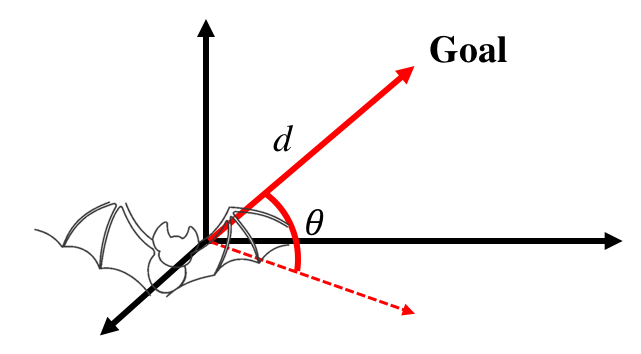

When moving through space we are often guided by goals (e.g. coffee). Dr. Ulanovsky has also examined how hippocampal cells code for spatial goals. This work, published in 2017 in Science, found in 3D space neurons can code for vectors towards goals including the vectors length as well as angle. This is coded by firing when the goal is a specific angle (theta in the figure below) to the bat. Further the firing rate for these cells increased as the bat approached the goal along the vector (angle) thus coding for vector angle and length. Two features in one neuron.

Many have posited that this codifying of space in the hippocampus and associated structures (i.e. medial entorhinal cortex, MEC) is not just a means of representing physical features but more generally any set of features. Dr. Aronov presented work examining this by creating a tasking using auditory cues, more specifically sound frequency, tied to a reward. This task therefore did not rely on spatial features. Rodents had to hold a lever down which triggered a sound to increase in frequency and to release the lever during a specific frequency window to receive a reward. By recording CA1 cells he found they coded for specific frequencies, even if the rate of frequency climb was changed to ensure it was not a coding of time. He was also able to identify cells in the MEC that coded for elements of the auditory task as well. If this sounds interesting, check his paper out in Nature from earlier this year.

An exceptional session showing we are still learning much about how the hippocampus and MEC code space as well as how these structures code for other features of our environment. Fascinating!

Patrick E. Steadman, MSc

PhD Candidate, Frankland Lab, The Hospital for Sick Children

MD-PhD Student, University of Toronto

Neuronline: @patrick.steadman

Twitter: @pesteadman

Blog: patricksteadman.ca/blog